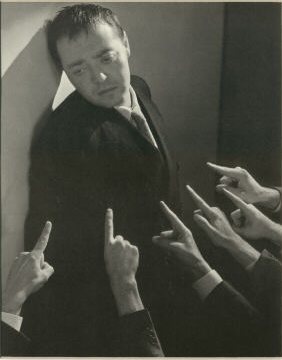

M has beautifil Camera angles! What an anticipation of film noir!  Fritz Lang did a brilliant job with the camera shots, the lighting, the flickering (even if that was unintentional, I loved it), and the story telling. M is a German film about a murderer (the brilliant Peter Lorre, pictured on the right) has the entire city searching for him, and the police are so invasive that the criminal underground decides the murderer is interfering with their business. So they search for the murderer themselves. When they find him a most interesting thing happens. They put him on trial in a kind of kangaroo court. Throughout the film before this, we weren't given any insight into the murderer's perspective. The director had sided the audience with the rest of the city. We are decidedly one of the "good guys" and we are pitted against (and searching for) the demonized murderer, the outcast, the scapegoat, the "other".

Fritz Lang did a brilliant job with the camera shots, the lighting, the flickering (even if that was unintentional, I loved it), and the story telling. M is a German film about a murderer (the brilliant Peter Lorre, pictured on the right) has the entire city searching for him, and the police are so invasive that the criminal underground decides the murderer is interfering with their business. So they search for the murderer themselves. When they find him a most interesting thing happens. They put him on trial in a kind of kangaroo court. Throughout the film before this, we weren't given any insight into the murderer's perspective. The director had sided the audience with the rest of the city. We are decidedly one of the "good guys" and we are pitted against (and searching for) the demonized murderer, the outcast, the scapegoat, the "other".

The murderer tries desperately to escape his trial, but he is forced to sit in. The mothers of the children he murdered shout, "Kill the beast!!!"

But the murderer demands a real court--he says he wants to be handed over to the jurisdiction of common law. The prosecution repsonds that he'll just be taken care of at the state's expense, and that he could just easily escape, or else get a pardon with his smooth-talking ability. And then "you'll be free, free as air", and because of his mental illness he'll be "off chasing little girls again."

"We must make you powerless!" the prosecution says, "we must make you disappear!" Then the murderer screams back in rebuttal, "I can't help what I do!" He doesn't want to kill people. It's just that apparently he cannot control himself. The ghosts of the victims' mothers chase him through the night, he says in his heavy German accent while heaving and almost frothing at the mouth.

Then the murderer screams back in rebuttal, "I can't help what I do!" He doesn't want to kill people. It's just that apparently he cannot control himself. The ghosts of the victims' mothers chase him through the night, he says in his heavy German accent while heaving and almost frothing at the mouth.

Someone in the peanut gallery shouts out, "That old story, that we cannot help it in court!"

Then Fritz seems to give the murderer a chance to explain himself. This is his spotlight. His true moment of real authentic living. True speech, as Heidegger would say.

And this is when our murderer accuses the criminals who are trying him of being guilty themselves. He is shamed into a sunken heap on the floor. But as he musters up some courage, he begins to rise up to give his speech. "Who are you? Criminals? Are you proud of yourselves," he begins. The murderer accuses the criminal underworld of not having any trade skills, just the ability to break safes and cheat at cards. He calls them a "bunch of lazy bastards." But he, of course, he cannot help himself. He has no control over murder. He must be schizophrenic?

"This evil thing inside me, the fire, the voices, the torment!" It's there all the time, driving him to wander the streets, following him, silently. But it is himself, he says. "It's me, pursuing myself." A man in the audience nods understandingly. "I want to escape, escape from myself! But it's impossible." He has to obey himself, and that means, of course, that he cannot stop being himself. (Unless of course he's dead.)

Somewhere in the course of filmmaking, someone decided that the topos for self-indulgence was rolling your eyes into the back of your head and having your mouth look somewhat frothy. Homer Simpson does this when he talks about "pink doughnuts". And Peter Lorre did this when he explains that he doesn't feel guilt only when he is murdering young children.

The prosecution: Someone who admits to being a compulsive murderer must be snuffed out like a candle.

During this underground trial, the defense is actually provided a well-spoken defense lawyer. The defense raises the point that the murderer had, that is, the prosecution is guilty of crimes themselves. In fact, the prosecutor is wanted for three murders. The defense claims that the murderer needs a doctor, not an executioner.

--What use are the asylums!

The prosecution storms ahead, about the execute the murderer. Then we hear another whistle, which happens all throughout this film. Everyone lifts up their hands in surrender. Then we see the hand of the law rest upon Peter Lorre's shoulder, and the police take the murderer into custody. Fritz Lang obviously held a very naive conception about the perfection of law. He didn't explain what happens after this. We assume that the same outcome was inevitable, that the murderer was sentenced to death. The mothers say "This won't bring back our children," as if to say that capital punishment doesn't serve any real purpose. The real courts and the Kangaroo court give us the exact same consequence, so what difference can there be, perhaps? And capital punishment is useless, and brutish.

we hear another whistle, which happens all throughout this film. Everyone lifts up their hands in surrender. Then we see the hand of the law rest upon Peter Lorre's shoulder, and the police take the murderer into custody. Fritz Lang obviously held a very naive conception about the perfection of law. He didn't explain what happens after this. We assume that the same outcome was inevitable, that the murderer was sentenced to death. The mothers say "This won't bring back our children," as if to say that capital punishment doesn't serve any real purpose. The real courts and the Kangaroo court give us the exact same consequence, so what difference can there be, perhaps? And capital punishment is useless, and brutish.

Such a brilliant film, from 1931, makes me want to see more films by Frtiz Lang, or starring Peter Lorre.

Monday, May 21, 2007

The Trial of the 1931 Film "M"

Submitted by

Acumensch

![]() at

21.5.07

at

21.5.07

Tag Cloud: Needs more art

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment